An exploration of retroactivity in music through Lacanian and Žižekian theory

I, the composer, wish to project into the future. I sit at the manuscript paper and I ask myself, “How will my piece end?”

The inevitability of the ending is something we may take for granted. Ultimately, there will be an ending: a fixed point of gravitational convergence in which the trajectories of a life (the life of a universe, a society, a person, an opus, a sentence) will reach their singularity. If we ask “how will it end?”, then we represent our desire for mastery of the future. Is that our own ability to master the future, or is it the future’s mastery of us? In wishing to know the end, do we not really ask for our future to be fixed, for the possibility of freedom to be erased? The question of “how will it end?” is a hysterical one.

“What the Hysteric wants” says Jaques Lacan (1969-70), “is a master”. Mastery is not within our grasp, it occupies the position of the other. In Lacan’s discourse of the Hysteric, a hysterical question such as “how will it end?” Is borne out of desire for the master signifier to produce knowledge. The knowledge which is produced by our question is mastered by the ending; the fact of an ending is an empty realisation. I say empty because the purpose of the ending is not to be the content, but to contain the content, much as a glass contains water. Everything which is not an ending is rich with interconnected meaning which conforms inexorably with the end. If we wish to know the end, we must look back rather than forward.

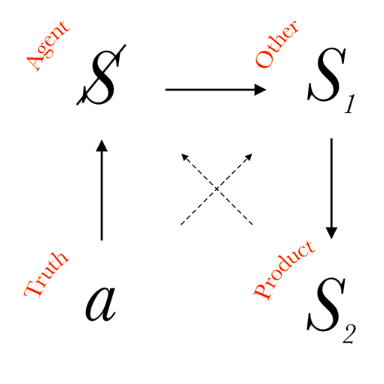

Fig. 1

Lacan’s Discourse of the Hysteric1

In the horizon of our future, we see the reflection of our past. That which we know we have done and which we know we have not done is the shape of what will follow. To put it another way, we can only do something of which we can conceive; present conception is a fertilisation of one past by another. I, composer, site of conception, have sought mastery of classical forms, I have sought access to the past, I have aligned myself with the dead. I, composer, site of conception, have allowed myself into servitude of the strange otherness which flows from the past, which escapes into my work in such a way that I am only the wall which fugitive past excavates into a tunnel. Past is the genome of present. Genes may function as determinant, but if they are the sole determinant then what can we cultivate? In a world which genetics forecloses, we may do nothing but procreate and die. Out of genetics and in opposition to it, we establish meaning which exceeds physical fact, we overcome physical boundaries in pursuit of goals which cannot be set genetically. Conscious past: a state of mastery and of calcified cul-de-sacs, of retreating shores of ever finer and finer knowledge; and Unconscious past: the Real beyond the knowable, the genome which boundaries our endeavours in ways we can’t ever fully understand. At the nexus of these two pasts, we find ourselves setting forth into the future. Observing identifiable past is the first step towards new interpretation. The next step is to understand there is another past which your historiology has not yet encompassed.

“According to the standard view, the past is fixed, what happened happened, it cannot be undone, and the future is open, it depends on unpredictable contingencies. What we should propose here is a reversal of this standard view: the past is open to retroactive reinterpretations, while the future is closed since we live in a determinist universe.”

Žižek, 2019

In composing the ending a piece of music, we re-compose the entire piece. The ending, though it means nothing in itself and it leads nowhere further, provides definition to the whole. If I have composed a chorale for SATB chorus in the style of JS Bach, and then I choose to finish the piece with an improvised drum solo, the meaning of the chorale is changed by the ending: the chorale is a chain of events which will lead inevitably to a drum solo. The same is also true if I choose to end, much more conventionally, with a Perfect Authentic Cadence in the choir: we read an inevitable progress towards the conclusion because we know what the conclusion will be. As composer, I do not compose the end of the piece at all: I choose an interpretation of the piece as it unfolds until that point, and then I allow the inevitable ending to happen.

Retroactive re-signification is of increasingly vital social importance in the field of music. For instance, when programming a concert, we must ask “How does this concert serve as master signifier? How does this concert contain and shape the past?” Asking this question should lead to two realisations: 1) our programming choices shape our relationship with music history and 2) this has always been the case, even when we were not aware of it. Ask yourself, for instance, “why are so few women composers programmed in concerts?”. The answer lies in the shape we give to the past. As Diane Peacock Jezic wrote in 1988:

“Because traditional musicology has tended to perpetuate study of “the great masterpieces” composed by “the great masters,” it has been musicians working in nontraditional disciplines (such as American music, black composers, or women’s studies) who have begun to reexamine the nature of musicology”

Jezic, 1988

Musicology gives legitimacy to itself via the “greatness” of the music it studies. The study of “great” music ensures the future of musicology and ensures the past of music: the canon of great composers is a tool for stifling the flame of new creations and inseminating the future with dead music. [The dead music I write about is present at the heart of much of my output, but then that would make sense genetically: many of my ancestors are dead]. Let’s work this through with an example. Heinrich Schenker, who wrote on composers such as Bach, Handel, Beethoven, Brahms, Bruckner and other germanic musicians from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, tells a story about music in which all music refers back to a few “great” composers. If, after Schenker, there is no interest in music which recalls those past composers, then there is no use for schenkerian analysis. Any adaptation of schenkerian analysis which allows for a greater diversity of composers to be analysed will create a dialectical path in which Bach, Beethoven, Brahms etc. must be recognised in the new composers who are to be considered (recognised by their absence, if not by their presence). Thus, at the heart of a schenkerian conception of what it means to be a composer, you will find those German men whom Schenker studied. Any successful musicology will restrict all music within its own bounds.

Jezic’s perspective shows a strong retroactive restructuring, both from the nontraditional musicians she cites and within her own evaluation of the past, which creates a nexus of choice. Do we choose the past of the “great masters” or the past of American music, black composers, women’s studies etc.? Programming a concert is an act of retroactive signification; the concert only has meaning in terms of the past which it organises; without history, music is meaningless.

“Our “Self’ is composed of narratives which retroactively try to impose some consistency on the pandemonium of our experiences, obliterating experiences and memories which disturb these narratives. Ideology does not reside primarily in stories invented (by those in power) to deceive others, it resides in stories invented by subjects to deceive themselves. But the pandemonium persists, and the machine will register the discords, and will maybe even be able to deal with them in a much more rational way than our conscious Self. For instance, when I have to decide to marry or not, the machine will register all the shifting attitudes that haunt me, the past pains and disappointments that I prefer to sweep under the carpet.”

Žižek, 2017

The composer is an ideological self of music. Music, organising the past, predicting the future, wells up from the unconscious, but is perverted into conscious form in service of a coherent composer-identity. In the Lacanian sense, composition must be a hysterical act in which the composer takes music as master signifier. A demand for creation from the master, definitionally a master which can not create, results in the composer creating for themselves and ascribing it to the master. Music is a product of misrecognition from the composer; the composer’s own desire channelled into the mouth of music/master signifier. Only in this form will a composer accept their own new creation: the creation is a piece of music or it is nothing at all. What goes unacknowledged, at least at first, is the excess which sits at the heart of the compositional process: the thing which a composer seeks to symbolise in music but which remains unsymbolised.

At this juncture, we can make some observations which will merit further consideration. A composer seeks to write music, and this is more true than the composer necessarily understands, as what they write is not a piece of music, but rather music is made from what the composer writes. Put another way, the past of music is rewritten each time a composer composes, rather than the future of music. If we allow the use of our Lacanian jargon, we can say that music occupies is a master signifier, and therefore its only role is to stand in as metonym for the signifying chain it contains. Furthermore, every concert is a rewrite of the past, re-historicising music and imposing a new master signifier. Creation, whether generative (composition) or curatorial (programming), is a hysterical act which exposes the master signifier and the knowledge which it organises. The social implications of this way of thinking should be clear; society is organised under master signifiers which can entail oppression and exclusion (as in Jezic’s observation of the musicological structures which fix a masculine understanding of composer. Self-conscious musical retroactivity implies a radical reassessment of the social construction which flows through signifiers of music history and allows for a rewriting of the past in order to change the path of the future.

1 In Lacan’s Discourse: “a” is objet (petit) a, the surplus enjoyment which cannot be resolved into the symbolic and which represents the object cause of desire; “$” is the barred subject, the incomplete and desiring subject of all discourse; “S1” is the Master Signifier, the empty signifier without a signified which gives order to the signifying chain which precedes it; and “S2” is all other signifiers and knowledge. The diagram of the discourse can be read as saying that the subject of the discourse of the hysteric is motivated by desire for a master, and the product of this desire is new knowledge.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Jezic, D. P. (1988). Women composers: the lost tradition found (2nd Ed.). The Feminist Press

Lacan, J. (1969-70). The seminar of Jacques Lacan: book XVII: psychoanalysis upside down/ the reverse side of psychoanalysis (C. Gallagher, trans.). https://www.valas.fr/IMG/pdf/THE-SEMINAR-OF-JACQUES-LACAN-XVII_l_envers_de_la_P.pdf

Žižek, S. (2017). Incontinence of the Void. The MIT Press

Žižek, S. (2019). Hegel, Retroactivity & The End of History. Continental Thought and Theory, 2(4), 3-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.26021/204.